Who is guarding Black culture? Seeking keepers in Tallahassee

Preserving Black history is a job for every generation.

Subscribe now

Episode 4 by Regan McCarthy, Assistant News Director

Edited by Lynn Hatter and Patricia Moynihan

Listen to the complete episode below. Subscribe now (by choosing your preferred platform) to be notified of upcoming episodes in this series. The text article below is abbreviated and may not include everything in the audio portion.

In the heart of Florida A&M University sits a stately, two-story white-columned building. Its architecture is distinct from other buildings nearby. The Carnegie Library was built in 1908—a gift from industrialist Andrew Carnegie to what was then the State Normal and Industrial College for Colored Students. It was built on the campus, after the city of Tallahassee refused the library because it would have had to also serve Black patrons.

Today, this 114-year-old building is home to one of the largest Black archives in the United States. Its shelves are filled with art, stories, and history by and about Black creators. The collection includes more than 500,000 archival records and more than 5,000 museum artifacts.

“I always had this motto, this saying, that if you write something in the sands of the beach today, when you come back tomorrow it’s gone because the waves washed it away. But if you carve something in stone, it will remain there forever. I always ask people, why do you think there’s a Mount Rushmore? Because they wanted that history of those forefathers to be remembered forever,” said Timothy A. Barber, director of the Meek-Eaton Black Archives and Museum.

He sees the white brick walls of the historic Carnegie Library where the archives are housed as their own kind of solid rock—preserving Black history so it can be remembered forever. That’s important, says Barber, because many would like to gloss over pieces of the past.

He continues, “History belongs to those people that are telling those stories and how they want those stories the be interpreted years from now is important. So, when people say, ‘We don’t want to hear Black history. We don’t want to talk about slavery.’ When people say, ‘We don’t want to hear primary source material about the experiences of people of color.’ That’s problematic because people would probably present slavery as being okay, and it wasn’t okay.”

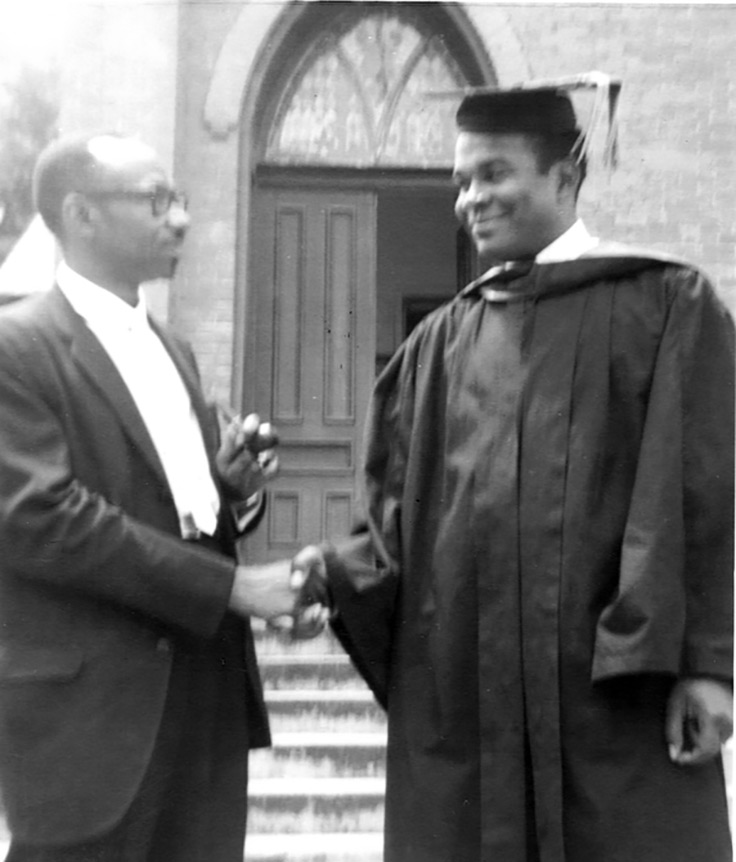

Barber started his job as archive director in July 2022, but this isn’t his first time there. While a student at FAMU, he trained at the archivesand some of his time there overlapped with founder James Eaton who established the archives in 1976. Eaton died in 2004.

“Dr. Eaton immediately began to collect things that were discarded, left out on the street. People really looked at it and felt that there was no use for it because the history of Blacks in America was not regarded as valuable,” shares Barber.

In 2002, Eaton spoke with The HistoryMakers, a nonprofit research and educational institution recording oral histories told by prominent African Americans. He said part of his goal was to amass source material and documents that would clear the way for authors and historians to detail American history through a Black lens.

If cotton was king, then the slave was the throne.

“Today, almost all of the major publications on Black subjects are done by white people because they get access to the records. And we don't have 'em. So what I decided to do, right, I'm gonna collect my own records. And that’s how we got started right here,” Eaton explains during his interview with The HistoryMakers.

During his time at FAMU, Eaton found many of his white students and colleagues preferred to ignore the more damning details of the country’s past. That ran counter to Eaton’s belief that “African American history is the history of America.”

“How in the world can you talk about the Old South and not talk about the history and contributions of African Americans? If cotton was king, then the slave was the throne. I always say that. If cotton was king, then slave was the throne because everything was based on the back of the labor supply.”

Eaton realized that safeguarding the full spectrum of American history required preservation and collection. In short, he and those who followed behind him, would need to become the keepers of their own history.

History belongs to those who write it

The first time John Due saw his future wife, Patricia, she was in Jet Magazine—a popular news source for Black readers during the civil rights movement.

“I decided I wanted to come down South where people were really involved in the movement,” said Due in a 2013 interview with WFSU.

Five months after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus two Florida A&M University students followed suit. Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson set off a city-wide bus boycott. Four years later, Patricia Stephens received national attention when she, along with her sister and a handful of mostly FAMU students, staged the first student-led “jail-in” in the country.

Due explained Patricia believed that ordering a piece of cake at a segregated Woolworth lunch counter should never have been a crime.

“She believed that paying for segregation was inhumane,” he continued. “She was arrested for a crime that she did not recognize as a crime, so why should she pay bail to be released? Because that is paying for an inhumane crime.”

At the time, Due was inspired by Patricia and the other students. He wanted to earn a law degree to help aid in the fight for civil rights. He decided to move from Indiana to Tallahassee to enroll at FAMU’s law school.

By 1963, John Due and Patricia Stephens were married. Together they raised three daughters and continued a life-long fight for civil rights.

Years later, the couple sat on a textbook selection committee in Miami Dade County.

“We were looking at the history textbook that was proposed and there was nothing in any of the history textbooks about the history of civil rights in Florida, and Patricia raised the question. And the response was ‘there's no history because nobody wrote it.’”

When Patricia was told there was no civil rights movement in Florida, “She was like ‘What!?’ So that was an eye-opening experience for her, not just to chronicle the stories of people she knew, Black and white, who sacrificed sometimes everything, even their lives, for the movement so history wouldn’t forget it,” said Tananarive Due, one of John and Patricia’s daughters. She says that experience spurred her mother to begin writing a book on the history of Florida’s civil rights movement. It wasn’t long before Patricia recruited Tananarive to help.

“I make the joke that I wrote the book so my mother would stop telling me the stories over and over—of the civil rights activists she knew from the 60s. But, she really was the self-designated griot and she kept telling us the stories. We kept hearing these names over and over again, like an eyewitness account to a part of history that she actually lived to see a lot of people forget,” Tananarive shares.

Tananarive is a former Miami Herald journalist turned novelist who writes mostly fiction and horror.

“The horror in my fiction is way less frightening and way less stressful than the horror of true-life history. The stories she was describing [were] the stor[ies] of people being shot at, being jailed, being arrested. In her case, being teargassed to the point where a police officer threw a teargas canister in her face when she was just a 20-year-old college student leading a nonviolent march—in Tallahassee by the way—in defense of students who had been arrested for sit-ins at lunch counters, trying to desegregate lunch counters. And because the officer recognized her as a leader of the movement, he threw the teargas canister in her face. As a result of that, for the rest of her life…she wore dark glasses indoors, 80% of the time.”

Together, Tananarive and her mother wrote the book “Freedom in the Family: A Mother-Daughter Memoir of the Fight for Civil Rights.” Due has published more than a dozen books and sees this one as her most important work.

“My mother was Patricia Stephens Due [and] my father, who is still living, is attorney John Due. They were my first real-life superheroes. So if I was going to write about any nonfiction topic, absolutely it would be them, but I have to give my mother credit. She was the one really, really pushing.”

Tananarive says those first-person stories are even more important now given the resurgence of overt racism, which would not have surprised her mother.

“This whole furor over what people call critical race theory used to puzzle me so much because I teach at the university level, and I've taught my students that critical race theory is something you learn in law school. It's about the interaction of the law and politics and it's sort of a complex idea. But I've come to realize that people who are afraid of critical race theory, for them, it just means anything that's critical about race relations—anything that makes the state look bad.”

Tananarive Due says her mother’s greatest fear was watching the clock turn back and seeing the rights she’d fought for be reversed.

“It is very clear that my mother was right about that, that the clock is turning back. And I've seen people in social media sort of wishing that that generation, or our generation, the Generation X generation, had had a better understanding of how fragile those gains were,” says Tananarive.

Stay Woke or Stay Sleep? The Language of Appropriation

Fifty-eight years after the federal Civil Rights Act was passed, there’s a new front opening in the ongoing battle for civil rights.

It's a war of words.

“This will put into statute the Department of Education’s prohibition on CRT in K-12 schools. No taxpayer dollars should be used to teach our kids to hate our country or to hate each other,” said Gov. Ron DeSantis during a December 2021 press conference-turned-rally where he unveiled a plan called the “Stop Wrongs Against Our Kids and Employees Act,” aka the Stop WOKE Act.

“This is something that you see all across the country and we have a responsibility in Florida to say ‘no, we’re not going to…scapegoat someone based on their race,’ to say that they’re inherently racist, to say that they’re an oppressor or oppressed or all that,” DeSantis said to cheers from attendees.

The law solidified a state ban on teaching critical race theory in K-12 grades and placed limits on how race and history can be discussed in public school classrooms and businesses. Multiple lawsuits against the law are making their way through the courts.

in this episode: featured song

- Sam Scriven, "We Must Believe"

- Performing for the 65th Anniversary Commemoration of the Tallahassee Bus Boycott

As the Stop WOKE Act was making its way through the legislature, Black lawmakers took active offense to it; they made passionate—and direct—pleas to their mostly Republican counterparts.

“We as a legislature have told Floridians you can’t protest, you can’t pass out water at precincts, you can’t play high school sports if you’re transgender, don’t unionize and now with this bill in this committee, we’re trying to tell you don’t tell your history. Don’t tell your perspective of what you think history is,” said Rep. Travaris McCurdy, D-Orlando.

Former Rep. Ramon Alexander, D-Tallahassee, briefly gained national attention when he effectively called the Stop WOKE Act racist and noted that a phrase used by Black people in protest of such policies was now being used against them.

“If race didn’t matter and this stuff didn’t poll well to get people to come out and vote and cause a dad gum insurrection, we wouldn’t have these types of bills,” Alexander said as colleagues attempted to cut him off.

Republicans, who largely backed the bill, tried to cast Black Democrats as not understanding what the measure was about. Rep. Patricia Williams, D- Broward, found those justifications patronizing at best, and insulting at worst.

“One of our colleagues said we’re confused about what we’re saying,” said Williams. “There’s no confusion about this. This is disappointing, this is disgusting for the state of Florida. Our history, it happened and we can’t take it back, but trying to cover it up to make someone that feels guilty not to feel guilty is disgusting.”

What repeatedly struck Black lawmakers was the language itself—clearly aimed at tamping down discussions of issues associated with the nation’s record of enslavement and civil rights that would make white people feel uncomfortable—issues that directly impact Black Americans.

“The study of race and racism has always involved language—specifically the public use of language and what does racism sound like, what is the vernacular of racism,” said Davis Houck, a professor of rhetorical studies at Florida State University. Houck says the language of racism has found its way into political speech where it’s used as a dog whistle to try to influence specific groups.

“And by dog whistle, this is just a fancy way of saying only certain people hear it in very particular ways. It’s a term loaded with meaning that only a particular group is going to hear,” he said.

Houck gives the example of former Governor Ronald Reagan campaigning for president in 1980 in Philadelphia, Mississippi where only 16 years earlier three civil rights workers had been murdered in a high-profile case. Reagan told a gathered crowd that he believed in state rights—Houck says by using that term, Reagan evoked arguments surrounding the Civil War and whether it was a fight to preserve slavery or to protect the rights of induvial states.

“Now, we’re not talking about states’ rights so much in 2022, but again, the vocabulary continues to evolve.”

DeSantis’ effort to turn a word prevalent in Black vernacular, the word “woke,” into a weapon, was a pointed shot—one Black lawmakers, local officials, and Black academics like Tallahassee Community College History Professor Dr. Andrea Oliver heard loud and clear.

in this episode: featured song

- Oshe Tyte, "ID"

- Oshe Tyte website | Follow on Instagram

“Who doesn’t want to be awake?” said Oliver. “I mean, what does that word really mean in the non-vernacular sense? It means to be enlightened; it means to be tolerant; it means to be aware. Who doesn’t want to be those things? So call me woke: I absolutely am. Because what’s the alternative? Sleep? Okay, so you’d rather me be asleep? And so again, we have to question the authorities and the powers that be. Why? Why does that [word] threaten you?”

Oliver posits the reason some would rather keep parts of the past hidden: it is because it doesn’t all follow the standard narrative most people learn in school.

“Why does the true knowledge, the full knowledge of this country’s history threaten you? Are you threatened because you might learn, or more importantly your young people might learn, about Bacon’s rebellion of 1676 which set in place the racial framework around which we have operated as a country ever since? Are you afraid that if the young people learn that they will learn that race and by extension, racism has been a big ruse to keep the status quo in power? Because that’s what it’s been!” exclaimed Oliver.

Bacon’s rebellion was an uprising of Black and white indentured servants and Black enslaved people led by landowner Nathaniel Bacon in the English colony of Jamestown. Bacon was upset by what he saw as unfair practices and poor land distribution by the colonial government. Ultimately, the rebellion was unsuccessful but the possibility of indentured servants and enslaved people banding together raised alarms for wealthy plantation owners. The uprising resulted in the end of indentured servitude policies and an increase in the slave trade—setting the wheels in motion for institutionalized racism to take hold in what would later become the United States.

Sticks and Stones

The term “woke,” which DeSantis took for his bill’s title, has deep roots in Black music and language.

Huddie Leadbetter, also known as the musician Lead Belly, used the term in 1938 while talking about his song “Scottsboro Boys.” He warned listeners to be aware of the racial violence spreading throughout the South.

“I’d advise everybody to be a little careful when they go down there. Stay woke. Keep your eyes open,” Lead Belly said. And in 2008, singer Erykah Badu and Georgia Anne Muldrow brought the term into the 21st century with the song “Master Teacher.”

The idea of staying woke became tied more directly to the Black Lives Matter movement following the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. By 2017, the word had become so mainstream Merriam Webster updated its entry in the dictionary to reflect the usage change—defining the term as being “aware of and actively attentive to important facts and issues (especially issues of racial and social justice).” But in the years that have followed “woke” has been weaponized against the people who coined it.

Nicole Patton Terry is the director of the Florida Center for Reading Research at Florida State University. She says this isn’t the first time a word from Black creators has been turned against them, and it won’t be the last.

“We have a long history of that in this country,” said Patton Terry. “Really these are just dog whistle terms that are being politicized to rial up a certain segment of our population to believe certain things and act in certain ways that just simply are not true.”

She says there’s a rich history of creative language use in Black English. It stems from the need for survival. Enslaved people used coded speech to communicate messages they didn’t want their owners to hear or understand.

“Language became a tool that was used to hold onto family histories and traditions, to survive and engage in really harsh environments as a roadmap and a way toward freedom, to move toward freedom and having to use language as a tool in that way very likely prompted many Black people to be extremely creative with language in many ways because you had to and to some degree, that’s still true to this day,” she said.

It hurts says Patton Terry, when language so clearly Black, is turned against its very creators.

“We have had a tendency to use that piece of who Black people are in ways that are negative, in ways that actually promote other people, but not us. In ways that can be harmful and damaging and how can we just stop it? Can we just cut that out? I think the real answer to that question is whether or not we’re ever going to get over this racism thing. ” said Patton Terry.

Telling Black people to “get over it” is a complete dismissal of real, lived, and ongoing experiences of the way a person has navigated the world around them—socially, educationally, and politically.

Again, Tananarive Due, “I would just caution anyone out there who’s listening to this and who does feel uncomfortable about racial history, who does wish why can’t we just forget about all that and let it go? I would love if we could forget about all that, but we can’t.”

The inability to simply forget the past and move on from it is nearly impossible for many Black Americans because it’s directly influencing what’s happening now. She says the deep roots of systemic racism coupled with the resurgence of overt racism continues to control how Black people are viewed and treated in most aspects of everyday life.

“The history is playing out every day when we're looking for real estate, when we're trying to get bank loans, when we're our children are suspended at higher percentages at school than their white counterparts,” she said. “All of this has roots in history, and much of it is fear. Fear of reprisal, I think is number one. Fear of being outbred is becoming literally a part of our national conversation in a way that it should have been before, but now as the kids say that the ‘subtext is now the text.’ It's starting to pop out that there's this fear of being outbred. History is just so, so, SO vital, in order to understand the world we're living in, and also in coming up with solutions so that we can all march peacefully toward a future.”

Today’s conversations about race, class, history, and privilege in some quarters are couched in what’s called replacement theory—the idea that one race or ethnic group will replace the dominant one. It’s been a cornerstone of white supremacist ideology, and a dangerous one, that,according to the Anti-Defamation League, goes back to the early 1900s. The language of that ideology is becoming more mainstream and used recently in debates over immigration, abortion, and in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests—and the ensuing backlash that spurred Florida’s “Stop WOKE” Act.

“It’s not like we’re out here having a slavery party and just want to talk about it all day because it was so fun,” said Patton Terry. “But we want to talk about the celebration just as much as the things that were horrible because they matter. So, I think it’s very important for us to make sure that we can continue to understand our past so that we can inform our future.”

Utilizing the Memory of the Past for a Better Tomorrow

“History is not just supposed to be all ‘this was terrible. I feel so guilty. I feel so bad.’ We have to do more with the past than say, ‘we feel guilty, or we just feel bad about what happened.’ How do we take that knowledge of the past and roll it into creating a better future because of the lessons we've learned from it?” believes Tananarive Due.

We talk about King as though King is still here, right? We talk about Fannie Lou Hamer as though Fannie Lou Hamer is still here. Eventually, my daughter shouldn't be talking about someone of my generation.

Who will do that work—keep the stories of the past while visioning a way forward for the future? Who is imagining themselves as one of the leaders?

“We talk about King as though King is still here, right? We talk about Fannie Lou Hamer as though Fannie Lou Hamer is still here. Eventually, my daughter shouldn't be talking about someone of my generation,” said Dr. Reginald Ellis, a historian and assistant dean for the School of Graduate Studies, Research, and Continuing Education at Florida A&M University.

“She's only four years old. So hopefully when she's 40, we still won't be talking about what King would have said, we'll be talking about something or someone of this generation, what they did, what they would have said to help change the shape of what this nation will be for her children.”

Ellis says he looks forward to learning who those civil rights leaders will be. Tananarive Due says it could be any of us: “We do have the power to create change if we just believe in ourselves.”