Coming to terms with the Black Church's changing role

African American churches have long been social, political, and educational centers for many Black communities. But that role is evolving amid what some historians and sociologists are calling the "Third Reconstruction."

Subscribe now

Episode 5 by Valerie Crowder, WFSU All Things Considered Host

Edited by Lynn Hatter, Suzanne Smith, and Patricia Moynihan.

Listen to the complete episode below. Subscribe now (by choosing your preferred platform) to be notified of upcoming episodes in this series. The text article below is abbreviated and may not include everything in the audio portion.

Jacob Chapel was filled on a Sunday afternoon in June amid the kickoff of the second Tallahassee Southside Festival. Worshippers clapped and swayed as the choir sang a rousing song of praise. Karen Gilispie basked in the moment.

“I’m Southside born. I’m Southside bred. And Lord willing, I’ll be here ’til I’m Southside dead,” she declared to applause and the chimes of a shaking tambourine.

Gillispie is a co-organizer of the festival. And in an interview after the kickoff service, she explained why a church was chosen as the place to get the annual arts and cultural festival underway.

“It’s been our education place,” Gillispie said of the church. “It’s been our political-movement place. It’s been our family-gathering place. It’s been places where we go to celebrate the home-going of our families. So, the church is just the heart of who we are because that was the only place we could meet, and be who we are. The church is the focus of our community.”

about the american periods of reconstruction

- First Reconstruction: marks the period immediately following the end of the Civil War, which saw the defeat of the Confederacy, the emancipation of formerly enslaved people, and the rise of new laws aimed at restricting Black peoples’ economic, educational, and social choices.

- Second Reconstruction: also known as the civil rights movement. This is the period starting from the end of WWII through the late 1960s (1948-1968). It culminated in the end of legal and government-enforced racial segregation.

- Third Reconstruction: some historians and sociologists are marking the election of President Barack Obama as the start of the third reconstruction, which also covers the rise of racial and social justice movements like Black Lives Matter and its ensuing backlash.

The Black church has historically served as a refuge for Black Americans living in a racially oppressive society. It’s been a safe haven for centuries, says local singer Anita Franklin.

“The church is what kept us” she said. “It’s that corporate gathering, whenever you come together and sing songs of Zion, not only to give praise to God, but we edify one another. It’s those trying times that the Black community have experienced, those trying times of racism.”

During a televised interview on NBC’s Meet the Press in 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. said, “I think it is one of the tragedies of our nation, one of the shameful tragedies, that 11 o’clock on Sunday morning is one of the most segregated hours, if not the most segregated hour, in Christian America.”

“In some ways that statement is challenging the sort of American Christian churches to live up to those central precepts or those central ideas of Christianity, maybe through the moral exemplary life of Jesus, the Christ,” said Jamil Drake, a former professor of religion at Florida State University who now teaches in the divinity school at Yale University.

More than 60 years after King called for church integration, Black and white churchgoers still worship separately. A Lifeway Research survey of pastors taken in 2021 shows 76% of church congregations have one dominant racial group.

“In some ways, race or whiteness still governs how people orient themselves religiously,” said Drake.

Churches are gradually diversifying, but those congregations are typically led by white pastors. Some African Americans are leaving the Black church—but other racial groups aren’t joining at the same rate of those departing. And historically Black-led churches are also facing another challenge: the departure of younger adults, especially Millennials and Gen-Zers, causing the institution of what’s known as the Black church to enter a period of transition.

Part II: Tallahassee's Black Churches and the Civil Rights Movement

What’s colloquially called the Black church began to emerge in Antebellum America, a time that spanned after the War of 1812 and before the Civil War. During this time, at the peak of the American slave trade, what would eventually become the Black church began to emerge. At that time, it came in the form of praise houses, says Drake, “small wooden clapboard structures,” that served as meeting spaces for the enslaved who eventually “create religion and in particular, Christianity on their own terms.”

Drake has written about its origins in his recently published book: “To Know the Soul of a People: Religion, Race, and the Making of Southern Folk.”

The Black church is a place where “people who have been dirtied, where they can affirm themselves, where they can affirm their humanity.”

“They actually served as sites where African Americans created Black religion and Black Christianity through various rituals, through various practices, through their various sort of vernacular culture. ”

Drake explains how the praise houses and hush harbors and secret worship gatherings of enslaved people blended African cultures with Christianity.

“The significance of these praise houses basically reside in the fact that African Americans—we should say, the enslaved—they get to practice religion apart from this surveillance of white owners and overseers.”

This foundational independence is something Black churches would continue to maintain in a society with a long history of oppressing African Americans. In the post-Antebellum period throughout the 20th century, praise houses evolved into centers for social life.

“On one level, they would serve as information bureaus to, in some ways, inform and alert congregants on the life and happenings of what's going on in the community,” said Drake.

During the Jim Crow era the churches functioned as what sociologist and author E. Franklin Frazier called “a nation within a nation.”

Praise Through Dance

“In other words, they're operating like the state because African Americans cannot depend on the state during segregation, because the state doesn't have their best interest in mind,” said Drake.

That’s why Black churches were not only sites of worship and spirituality, but places where African Americans could get basic services they couldn’t receive elsewhere like childcare, education, settlement houses for the poor and health clinics.

In a 1980 interview with WFSU, Dr. James Hudson, the chaplain at Florida A&M University at the time, said he believed “the church has historically represented, in the Black community, more facets of community life than any other organization.”

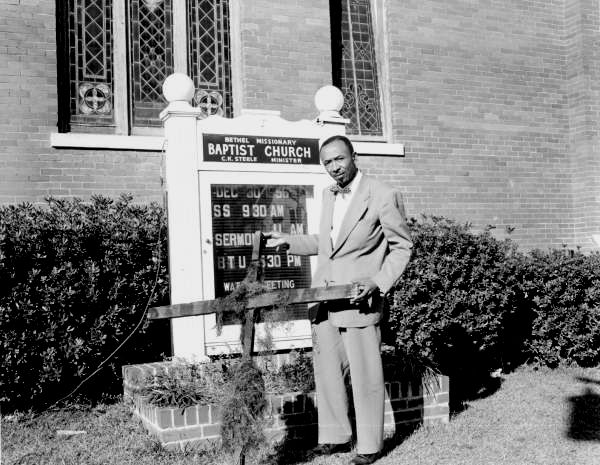

Hudson worked with Bethel Missionary Baptist Church’s Rev. C.K. Steele to rally the Black community to the Tallahassee boycott cause in 1956. In a 1979 interview with WFSU, Steele talked about leading Bethel during boycott. That church served as the community gathering place.

“We called a meeting of leaders. We appointed a committee to go see the city manager and the manager of the bus company, to see if we could get some understanding, which we did not get,” he said.

Steele says the local boycott wouldn’t have happened without the leadership of FAMU students—who started it after being inspired by the boycotts in Montgomery, Alabama. Local Black churches like Bethel later got involved.

“We reported at a mass meeting that night, at which time they [attendees] voted to come off the buses, which demanded some kind of organization. [The] NAACP had been banned in Alabama, and so there was a fear that it would be banned in Florida. So, they [local clergy] decided to organize a new organization called the Inter-Civic Council and I was elected as its first president.”

One of Steele’s sons, Henry Marion Steele, was a boy when the meeting happened in 1955. In a 2013 interview with WFSU, the younger Steele described what it was like to be there. Hundreds of city residents attended the first meeting.

“The church was packed,” he said. “No parking spaces on the lot or around the block anywhere. Cars were everywhere, and people [were] almost hanging out the windows, so to speak. But at that meeting they elected their offices, at which time they elected my father president.”

Steele said of his father, C.K., “My dad was a very dedicated and sincere person, and he was forceful, he was dynamic, he was humble. He was the right person to negotiate.”

Though the Tallahassee Bus Boycott received less attention than other desegregation protests, it played a significant role in influencing the very early stages of the broader civil rights movement, and at the forefront of it was the church.

Black religious leaders’ involvement in the fight for racial justice was widespread, says Florida-based historian Gregory Padgett.

“Martin Luther King was an exceptional African American religious leader, but he was not unusual. There were a lot of them.”

Padgett is a historian at Eckerd College in Saint Petersburg. He earned a Ph.D. in history at Florida State University. While at FSU Padgett attended Bethel Missionary Baptist Church, where C.K. Steele was his pastor.

“The only institution in which African Americans had in total control was the church. And so African American ministers had an autonomy that other folk did not have,” Padgett said.

In the 1950s most of Tallahassee's African American residents lived in poverty. Padgett says ministers were able to operate independently from the city's economic system because they had the financial support of their congregations. He wrote about that period in the book, “Sunbelt Revolution.”

“In my little article, there was the talk of the tripartite—three kinds of legged forms of oppression: economic, personal and political. And because they did not look to outside forces for their income, African American ministers were sort of immune from that.”

That economic independence coupled with its unique founding would enable the Black church to provide an anchor to the civil rights movement

The Black church is a place where “people who have been dirtied, where they can affirm themselves, where they can affirm their humanity,” said Yale’s Drake.

“That's a very revolutionary idea, particularly when you're in a context where Black people are called everything but human. So here, we can go to a space where we're being taught that we're somebody. We can go to a space where we're taught that we're God's children, that we have value [when] the world is calling you is completely wrong.”

Part III: The Church’s Evolving Role in Society

Today, a new movement has emerged—one that has taken aspects of the civil rights movement and is pushing it beyond race, and away from the church. It is the Black Lives Matter movement and Padgett says “it’s not the context the we are accustomed to or the civil rights movement in the way we learned to recognize it.”

Ten years ago, a 17-year-old Black teen was shot and killed in a Sanford, Florida neighborhood. He’d been followed home by a self-appointed neighborhood watchman who was suspicious about why Trayvon Martin would be walking down the street. When George Zimmerman was found not guilty of killing Martin, protests across the country broke out. Eight years later, #BlackLivesMatter would become an anthem when George Floyd was murdered by a police officer—setting fire to long simmering racial and social fault lines.

But this time, unlike the civil rights movement, the protests had new faces: a broad and multiracial coalition of young people, women, LGBTQ, Black, white, and brown. Together protesting, marching, and calling out the social inequities that go beyond race, all while the Black church, accustomed to leadership, found itself playing catch-up. Padgett cites the work of Robert Brisbane, a former historian and social scientist at Morehouse College, who wrote about the early civil rights movement and captured the cyclical nature of racial justice movements in his book “Black Activism: Racial Revolution in the United States, 1954-1970.”

“I don’t think Brisbane is still alive,” Padgett said, noting Brisbane died in 1998, “[but] I’d love to see what he would do with the Black Lives Matter, which for some of us older folk, we sort of scratch our heads because it’s not the context we are accustomed to or the civil rights movement in the way we learned to recognize it.”

Leadership in social justice movements today are decentralized, whereas, says Padgett, “leadership up until the 1980s, for that kind of activity in the African American community, always came from the church.”

Padgett notes secular groups have long worked alongside the church in the fight for justice and equality—but the church had always held a prominent role in those efforts.

“The best and the brightest [are] no longer in the ministry, not that there aren’t some there. But not in the number, with the single-mindedness that I witnessed growing up. [It’s] very different,” he said of today’s movements.

When Leon Sheriff Walt McNeil rolled out his Allin LEON crime reduction initiative several years ago, he emphasized partnerships with Black churches as a cornerstone of his effort to reduce gun violence in the county. According to the Leon Sheriff's Office most gun violence victims and perpetrators are young Black men and boys. Today, McNeil has de-emphasized the church involvement part of his plan, and he’s blunt about why.

“Just being frank about it, I don't believe in doing the same thing over and over. And the church angle has been used for the last 40 years with little to no success,” McNeil said of tying crime reduction to church involvement. Yet that doesn’t mean he has abandoned church partnerships completely.

“I do believe there are places where the church has a significant role to play. In that respect, I have an initiative here that we call ‘worship with me.’ And through that process, we will continue that as one of our efforts, where we try to engage again with the family. And it's not a specific denomination or type of worship. It's any family that would like to be churched or would like to have a religious experience. We will try to facilitate that if the parents believe that that's going to be helpful in their circumstance. But it's not something that we believe has universal application as a way of preventing crime, quite honestly.

The influence of the Black church is declining. Nearly half of African American Millennials and Gen-Zers seldom or never attend church. That’s from a PEW study on faith and religion among Black Americans done in 2021. That’s similar to other people of different races.

“They view Christianity as a white supremacist institution,” said University of Houston Religious Studies Professor Aswad Walker of younger people who’ve left predominately Black churches. “It’s the same view some young Black activists had in the 1960s when they looked at the Black church and said ‘this is an Uncle Tom’ Institution. It is not serving the interests of Black people’ and so many people during the sixties moved away from the church because they didn’t see it working for Black people.”

If Christians can preach that God made us perfect and God knew us before we were born, [then] why do I gotta pretend and put myself in a box if this is how I’m supposed to be?

Walker says one reason for the decline in participation is the church’s emphasis on tradition, instead of progress.

“We do this today because we’ve always done it this way,’ and that’s an issue for young folk who are always pushing the boundaries. The other issue is that a lot of Black churches—not all but a lot—have stances on women and stances on LGBTQ issues that do not coincide with where young people are today.”

“If Christians can preach that God made us perfect and God knew us before we were born, [then] why do I gotta pretend and put myself in a box if this is how I’m supposed to be?” asked 29-year-old Jeremiah House. House says he left his predominately Black church when he turned 18.

People like House who’ve left the church are finding community elsewhere. He identifies as queer and grew up in rural Liberty County. He attended a local Missionary Baptist Church throughout his childhood. In high school, he moved to Orlando with his aunt and uncle and continued to go to church.

“I knew that church wasn’t going to be a thing for me anymore at the age of 17 after hearing that the hatred and the fear that was being taught and put on people. I just knew that wasn’t the God that I served.”

House says he didn’t feel welcome at church as a member of the LGBTQ Community, so he left, but still believes in God.

“Something here doesn’t make sense, and if it ain’t making sense, I’m not finna try to add it up. I’m going to take the meat. Ya’ll can have the potatoes,” he said, speaking metaphorically about what he views as the fear of and discrimination against LGBTQ people in some predominately Black congregations (the potatoes), versus his personal belief in the teachings of Christianity (the meat).

Now, House is in between different forms of spirituality, including ancestor veneration, divination, traditional medicines for healing and folk practices. He describes himself as intuitive. He says while he can sense light, he also senses darkness and he describes the feeling he gets at Railroad Square, where this interview was conducted, as “eerie.”

“We are in the South—the rural South—the Bible Belt. There have been a lot of souls that have transitioned here in very negative ways, maybe ways that were unjust. There have been fights for liberation here, fights for freedom here. Where there’s darkness there must be light, and vice versa. Tallahassee is a very beautiful place, but the history here, if you know your history, I feel like you can’t help but feel eerie in certain places.”

Ways of Worship

journey through this photo of himself immersed in the waters of a creek at his home. (Right/Bottom) A person dressed in black uses mime to express a veneration to God during a Sunday service at Bethel Missionary Baptist Church.

Part IV: The Church’s Role Today

For decades, Tallahassee’s Bethel Missionary Baptist Church has been at the center of the fight for social justice. Today, the historic church continues to serve as a gathering spot for elected officials, community leaders, and clergy members to discuss issues like voting rights, gun violence, and criminal justice reform.

“Today we call on the Senate to stop filibustering around and pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Amendment,” preached Orlando-based Pastor Marcus McCoy at a voting rights rally at the church in September of 2021.

“Today we call on our own state legislators to share how they are going to ensure that our upcoming redistricting process is conducted fairly and invites the voices of the people around our state to be heard,” he said.

McCoy also called on state lawmakers to be fair in the redistricting process. Gov. Ron DeSantis would later go on to eliminate two Black-controlled districts, including the seat held by Congressman Al Lawson.

“Today we call on the over 14 million registered voters in the state of Florida to get out and vote in every election. Today we move from apathy to accountability, from complacency to tenacity, from we can’t—to we will,” he said as worshippers clapped in agreement.

More recently, about 300 people from local congregations packed the pews at the Old West Primitive Baptist Church’s Enrichment Center in Tallahassee in the spring of 2022. Their goal? Persuade local officials to fund efforts to reduce gun violence, and increase affordable housing.

Those two issues disproportionately affect minorities and low-income people. Ministers from more than a dozen local congregations spoke during the program, including Rabbi Michael Shields, who’s also co-president of the Capital Area Justice Ministry.

"You" know what? We’re like the tribes of Israel—we’re all a little bit different, but we’re all justice people. One people united in justice. And tonight is the culmination,” Shields said.

Reverend James Houston is a minister at Bethelonia AME Church in Tallahassee and is also the co-leader of the Capital Area Justice Ministry.

“We have meetings within our community and within our churches, and the major issues that came up after we did all of the house meetings was gun violence and affordable housing. And the gun violence because we all know people who’ve been affected by the gun violence. So it’s very important that we keep our kids alive and we keep them out of jail if we can.”

Houston spoke with WFSU after the Capital Area Justice Ministry’s call-to-action event. Several city leaders were asked on stage whether they’d support more funding for gun violence reduction and affordable housing.

“We got a lot of wins, we got wins on the criminal justice side. We didn’t get all that we needed from the housing. We got two out of the five commissioners to go with us on low-income rental housing, we needed at least three, but we didn’t get it. I know the greatest need for this community right now is low-income rentals,” he said.

Sixty years after Martin Luther King Jr. issued his call for religious integration, Black and white people still tend to worship separately on Sunday mornings. Pastor Darrick McGhee of Tallahassee’s Bible Based Church noted that when he stepped up to the podium.

“Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said the most segregated day of the week is Sunday morning. You cannot see justice come to pass if we do not discontinue looking at each other in a different manner,” McGhee said, calling attention to the paradox and making a plea for religious unity.

“I believe tonight, if we come together, the one I believe in will make sure we see the one thing we all want to see, which is JUSTICE!”

Today, political hopefuls continue to flock to Black churches—a recognition of their ongoing power and influence of Black communities. These same churches, notes Yale’s Drake, were at the forefront of vaccination efforts against COVID-19 and combating misinformation by spreading the word to the very people most at-risk of dying from the virus.

“If we think about Black churches here in Tallahassee, when we think about the pandemic and vaccines they're not just serving Black people or their congregants. They're also serving non-Black people, too. And I think that's a very important point, in terms of a vibrant, prophetic and democratic tradition coming out of the Black church, where it's not only serving the needs of its congregants, but also the broader community, even people who do not look like them.”

Local Gospel music singer Anita Franklin grew up in the Greater Love Church of God in Christ on Orange Avenue on Tallahassee’s Southside. That’s the church her mother founded when she was a girl. Franklin, who turned 60 this month, explains how music—particularly Gospel music—has brought joy to Black people in America in times of immense hardship.

“Through those years of our ancestors who have suffered and have died and have been abused, but they had that spiritual part that kept them, just embracing who God is, to keep them strong through those times of going through torture, just going through lynchings, going through families being broken apart.”

And Sheriff McNeil, who is continuing his effort to rescue Black men and boys, continues to acknowledge the church’s worth and value in keeping, and building community.

“So the religious component is there. But again, I believe it's applicable, where it's like faith, if you don't seek it, it has no value.”